Did you know that Walt Disney’s The Jungle Book is the most successful movie of all time in Germany? In its original theatrical release there, The Jungle Book sold up to 27.3 million tickets and made an estimated $108 million in that country alone! That’s more tickets sold in Germany than both James Cameron’s Titanic (1997) and Avatar (2009)! [1] In addition, on its original theatrical release in the USA on October 18, 1967, the film made back $73 million on a $4 million budget, making the second highest grossing film that year, second only to The Graduate (1967). The film was also re-released in theaters on 1978, 1984, and finally summer 1990, to coincide with TaleSpin, a Disney Afternoon show which featured characters from the movie, which was set to premiere on television later that fall. All in all, The Jungle Book made up to $141 million domestically and about $205 million worldwide. Adjusted for inflation with an estimated $655 million, however, The Jungle Book is the 32nd highest grossing motion picture of all time in North America and the 5th highest grossing animated feature ever made. The movie was first released on VHS in 1991, when it featured a special behind-the-scenes trailer for the then-upcoming Beauty and the Beast (1991). The video sold up to 14 million copies by January 1994. It was released on video again in 1997, to mark the film’s 30th anniversary. The film was released on a 2-disc Platinum Edition DVD on its 40th anniversary in 2007 and was released on Blu-ray for the first time in 2014.

Despite being a critical and financial hit and being beloved by children and families everywhere, the film itself has very little resemblance to the original books it was based on. The original Jungle Books, published between 1894 and 1895 by British author Rudyard Kipling were a collection of several stories involving the interaction between men and animals, including “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi”, the story of a mongoose who protects a human family from a pair of wicked cobras and “The White Seal”, about a rare white seal who journeys to find a new home for his people to avoid being hunted by men. Disney’s version, along with most, if not all, adaptations of the two books are based off the stories involving the adventures of a “man cub” named Mowgli and his animal friends and enemies. Out of all 15 stories including in the Jungle Books, 8 of them were Mowgli stories: “Mowgli’s Brothers”, “Kaa’s Hunting”, “Tiger! Tiger!”, “How Fear Came”, “Letting in the Jungle”, “The King’s Ankus”, “Red Dog”, and “The Spring Running”. Among the most notable differences were the fact that Kaa the python is as good a friend to Mowgli as Baloo and Bagheera. Kaa was changed to being a minor antagonist hell-bent on devouring the man cub in the Disney film because Walt himself thought American audiences wouldn’t accept the idea of a snake being a heroic character. Elsie Kipling Baimbridge, the daughter of Rudyard Kipling, also claims the name “Mowgli” is supposed to be pronounced “MAU-glee” (As in the first syllable rhymes with ‘cow’) . In the film and almost all other adaptations of the Mowgli stories, the name is pronounced “MOH-glee” (As in the first syllable rhymes with ‘go’). The only adaptation so far to get the pronunciation of Mowgli’s name right is Chuck Jones’ 1976 animated TV adaptation of “Mowgli’s Brothers”, which remains completely faithful to Kipling works unlike Disney. There are also several characters from Kipling’s books who never appear, including Tabaqui the jackal. who was Shere Khan’s minion, Mao the peacock, Chil the kite, Buldeo the village hunter and Ikki the porcupine, (who does appear in the 2016 live-action version, voiced by the late Garry Shandling). The surprising number of differences between the Disney classic and Kipling’s stories are far too great to list in this article, so if you’d like read them for yourself, here are the links to the first and second Jungle Books by Rudyard Kipling.

Back onto the Disney film, Walt first expressed interest in making a film based on Rudyard Kipling’s books in the late 1930’s, but it wasn’t until 1962 when, at the suggestion of his most trusted story man Bill Peet, he bought the film rights to the novels while The Sword in the Stone (1963) was still in production. Before that, the only other direct film adaptation of Kipling’s Mowgli stories was a 1942 Technicolor adventure movie produced by Alexander Korda and starring Indian actor Sabu as Mowgli. Walt agreed to let Peet handle the story supervision of the film while he would merely produce the film. This had been done successfully before when Peet single-handedly storyboard the entirety of One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) himself! By this time, Walt became less and less involved with his new animated features as he was in the past and focused his time more on his television shows and theme park attractions, and so left his animated projects in the hands of his story department led by Bill Peet. Peet wanted to create a singular storyline in contrast to the episodic and inconsistent sorting of Kipling’s stories, but he still wanted to remain faithful to the dark, mysterious, drama-filled nature of the stories themselves, focusing on the struggle between man and beast. Peet worked on the project for over a year and was responsible for many of the key elements for the final version, including making Bagheera a serious and mature guardian for Mowgli, turning Baloo into a lovable carefree comic relief, and having the film end with Mowgli returning to his rightful place in the man village, whereas in the books, he goes back and forth between wilderness and civilization. Peet’s version of the story was also more perilous, with Mowgli constantly getting into danger. Peet created the character of King Louie as the leader of the Bandar-log (the Monkey People), who were originally leaderless in the book. Louie was also a much more villainous character in Peet’s version, who had his henchmen kidnap and force Mowgli to teach him how to create fire, or as the animals in the Kipling books call it, the ‘Red Flower’, the one thing all animals fear and hate most about man for its destructive powers. Louie’s villainous persona and desire to conquer the jungle with the Red Flower was further explored in Jon Favreau’s live-action/CG remake in 2016. Louie would also show Mowgli a vast pile of gold and jewels under the ancient ruins, which the man cub could care less about but men would destroy each other for, something lifted straight from the story “The King’s Ankus”. Another villain lifted from Kipling and included in Peet’s version of the story was the village hunter Buldeo, who seeks to kill the tiger Shere Khan and destroy the jungle. In Peet’s ending , after Mowgli uses the Red Flower to challenge Shere Kahn, Buldeo would learn about the treasure and force Mowgli at gunpoint to lead him to the ruins and take the gold for himself. Mowgli learns of Buldeo’s plot to kill Shere Khan by burning the jungle down and tries to stop him. Before Buldeo can kill Mowgli, Shere Khan attacks and kills the evil hunter, giving Mowgli the opportunity to take Buldeo’s rifle and shoot the tiger dead. Mowgli is celebrated by his animal friends as a hero to both man and animal and is allowed to come and go from the jungle and man village as he wants. In addition, Peet hired folk singer/songwriter Terry Gilkyson to write seven original songs which matched the dark Kipling-esque tone Peet was aiming for. Among the songs were “Brothers All”, the opening number which includes the Hunting Call “We are of one blood, you and I”, and “The Mighty Hunters”, which would serve as a villain song for both Shere Khan and Buldeo, each boasting about how much they hate and desire to destroy each other. You can listen to the original demo recordings to Gilkyson’s songs here and here. However, after expressing disappointment over the lukewarm reception of The Sword in the Stone (1963), Walt decided to become more personally involved with his next big project. Walt was also not happy with how The Jungle Book was turning out, feeling that no family audience could stand the grim, dramatic Kipling-esque tone Bill Peet was aiming for and insisted that the treatment be changed. Peet refused and after fighting with Walt over story issues, Bill Peet left the Disney studio in 1964 after working there for 27 years. He became an author and illustrator for children’s books for the rest of his career.

With Bill Peet out of the picture, Walt then assigned Larry Clemmons, a former writer for Bing Crosby on his radio programs, as the new head of the story department. Walt also assigned Wolfgang Reitherman to direct the film. Before directing, Reitherman was previously an animator specializing in fast-moving or intense action sequences. For example, he animated Monstro the whale in Pinocchio (1940) and the climactic battle between the Stegosaurus and T-Rex in “The Rite of Spring” segment of Fantasia (1940). His first directing job was on Sleeping Beauty (1959), in which he supervised the film’s epic climax, involving Prince Philip taking on Maleficent in dragon form. He then co-directed One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) with to other directors before becoming the single director of every Disney animated film between The Sword in the Stone (1963) to The Rescuers (1977). The first thing Walt said to his staff was to “take the book, and not read it.” Walt did not want to focus on the dark serious aspect of Kipling’s works but to focus more on characters with wonderful personalities against an exotic setting. With that in mind, he told his writing staff to “do the meat of the picture. Let’s establish the characters. Let’s have fun with it.” And that’s just what the staff did. Only basic elements from Kipling’s works were featured in the now simple storyline driven by fun characters, with Mowgli being raised by wolves from “Mowgli’s Brothers”, the man cub getting captured by monkeys in “Kaa’s Hunting”, and confronting Shere Khan and going back to the man village from “Tiger! Tiger!”. Although most of Peet’s material was scrapped, the personalities he gave to the characters were kept along with a new ending in which Mowgli is seduced by a beautiful young Indian girl fetching a pail of water, leading him into the man village, an element borrowed from “The Spring Running”. Animator Ollie Johnston, one of Walt’s best animators, initially hated the idea and tried to talk Walt out of it, but was given the assignment to animate the scene anyway. The more he worked on the sequence, the more he grew to like it and realize it was the best way to end the film without resorting to a tear-jerking goodbye. All of Gilkyson’s songs were cut too, except for one tune for Baloo called “The Bare Necessities” which Walt and the crew liked, but at their suggestion, Gilkyson gave it a faster tempo, a different chorus and rearranged some verses and thus a classic Disney song was born. New songs for the film would be written by brothers Robert and Richard Sherman, who remember seeing the 1942 film with Sabu. The Sherman Brothers had previously wrote the songs for The Sword in the Stone (1963) and won two Oscars for their musical work on Mary Poppins (1964). Speaking of which, Kaa’s song “Trust in Me” was originally written for Mary Poppins under the title “Land of Sand”, but was cut from that film and repurposed for The Jungle Book. The vulture’s song “That’s What Friends Are For” was originally done in the style of a rock song at the time, but Walt thought it would date the film, so the brothers rewrote the song in the style of a barbershop quartet to make it more timeless. Back in those days, animated features didn’t have screenplays written prior to voice recording and animation. To develop the story, the staff would have story meetings, in which Walt would act out each role and help to explore the emotions of the characters, develop emotional sequences and comical gags. Clemmons would write a rough outline for every sequence and the story artists would then create storyboards with dialogue pinned underneath. In other words, this was done so that the story could be driven by what’s going on visually. Even though Walt put all his heart and soul into the film, he never lived to see his creative vision on screen, because on December 15, 1966, 10 months before the film’s release, Walt Disney passed away due to complications from lung cancer, making The Jungle Book the last animated feature with his personal touch. When the completed film was first screened at the studio, Walt’s personal nurse Hazel George had tears in her eyes upon seeing the final shot where Bagheera and Baloo walk off into the sunset. She came up to animator Ollie Johnston telling him that it was just the way that Walt had gone out.

When it came to casting the film, this was one of the earliest animated features to cast big-name celebrities (at the time) for voicing the majority of the cast, which has since become the norm for all animated films today. The cast helped to shape the final designs and personalities of the characters. Jazz singer and comedian Phil Harris, the voice of Baloo, ending up improvising most of his lines because he felt the script he was given “didn’t feel natural”, but this made his character all the more believable and memorable. Bagheera was voiced by Sebastian Cabot, best known for playing Giles French on the CBS sitcom Family Affair and for narrating the Winnie the Pooh featurettes. Originally, the staff considered jazz performer Louie Armstrong for the role of King Louie, but quickly realized that having an African-American playing an ape would be in bad taste, so they instead hired the ‘King of the Swing’ himself, Louis Prima, a famous jazz singer and bandleader of Italian-American descent. If Kaa’s voice sounds strangely familiar, it should. That’s because he’s voiced by longtime Disney collaborator Sterling Holloway, who voiced Mr. Stork in Dumbo (1941), the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland (1951), and was the original voice of Winnie the Pooh! He even recorded his lines for Kaa after finishing his sessions for Pooh. Kaa was originally meant to only appear once, but proved to be so popular with test audiences that he was given a second major scene. Other Disney regulars included J. Pat O’Malley as Colonel Hathi and Buzzie the vulture and Verna Felton as Winifred, Hathi’s impatient wife. Felton had previously voiced the Fairy Godmother in Cinderella (1950), the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Flora in Sleeping Beauty (1959). This would also be her last film for she died December 14, 1966, exactly one day before Walt Disney’s death. Mowgli was originally supposed to be voiced by David Alan Bailey, but his voiced changed and the crew needed a replacement. Luckily, Wolfgang Reitherman brought in his own son, Bruce Reitherman to voice the man cub. Bruce was also the voice of Christopher Robin in Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree (1966). Oddly enough, Bruce Reitherman is now a wildlife documentary filmmaker. For Shere Khan, artist Ken Anderson depicted him as an conceited and sophisticated gentleman to make him more menacing, while supervising animator Milt Kahl refined the character’s design. With that in mind, several actors including John Carradine, Hans Conreid (Captain Hook from Peter Pan), Claude Rains, Vincent Price, Basil Rathbone and Boris Karloff were considered for the voice of Shere Khan [2] before they settled on George Sanders. Sanders had previously won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance in All About Eve (1950), making him the first Oscar-winning actor to voice a character in a Disney animated feature.

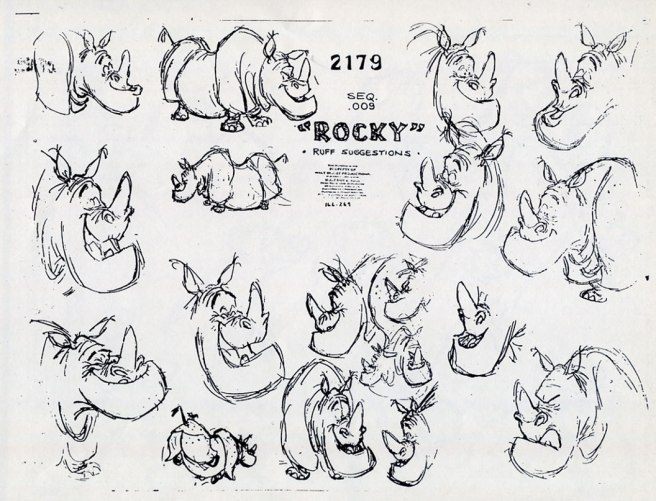

Out of all the colorful characters in the film, there was one created for the film who never had his chance in the spotlight: Rocky the Rhino. Rocky was designed as a near-sighted dimwit with punch-drunk boxer personality. Frank Fontaine, best known for playing Crazy Guggenheim on The Jackie Gleason Show, was brought in to voice the character. Rocky was supposed to fight Mowgli after the vultures force him to challenge the slow-witted beast and, as expected, hijinks would ensue from there. After Mowgli defeats Rocky by outsmarting him, the vultures and the rhino would become friends with Mowgli, leading to the song “That’s What Friends Are For” and the final confrontation with Shere Khan. The character had gone so far as to have model sheets ready for the animation process by the time he was cut from the film. Walt decided that having one action scene on top of another wasn’t very good storytelling, and the monkeys and the vultures were already enough to handle. Even though Rocky never appears in the final cut, he can still be seen in Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971) as an extra in the crowd watching the soccer match in the Isle of Naboombu. Also in the 2016 remake, there is a rhino character voiced by Russell Peters who is listed in the credits as ‘Rocky’.

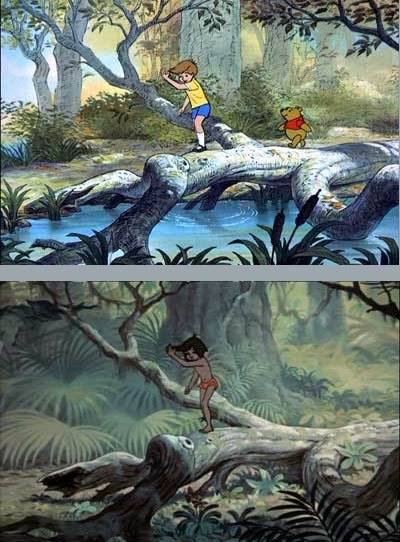

For the animation on the film, unlike supervising animators in later films who were assigned to one character, supervising animators at that time were responsible for entire sequences, so it was common for one animator to draw two characters interacting with each other. Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston mostly worked on scenes involving Mowgli and Baloo. The two had a career-long friendship and it is reflected with Mowgli and Baloo’s friendship. Milt Kahl was responsible for the final character designs by refining sketches given to him by concept artist Ken Anderson. For scenes with Bagheera and Shere Khan, the two big cats of the production, Kahl studied live-action footage of big cats in action from two other Disney films, A Tiger Walks (1964) and the True-Life Adventure film Jungle Cat (1960) as reference. The waterfall seen in the opening after the credits is live-action footage of a real waterfall, Angel Falls in Venezuela, integrated with the hand-painted background through optical effects. By the 1960’s animation began to cost more and more money to produce, so the crew had to figure out ways to produce top notch animation at a lower cost and without sacrificing quality. One major solution was the ‘Xerox process’. Originally developed by Ub Iwerks and first used in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), the ‘Xerox process’ involved using early Xerox photocopy machines to copy the animator’s drawings and print them directly onto sheets of celluloid. This eliminated the expensive and time-consuming process of tracing the animator’s cleaned up drawings onto cels with ink by hand, though some details like the man village girl’s lips are still hand-inked. This also gave the characters rough, hard sketchy edges on their outlines, instead of the soft, rounded colored lines of previous Disney characters. Another method done to keep costs down was to retrace animation from previous films. The wolf cubs were traced over the animation of the Dalmatian puppies from One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), Mowgli being licked by his wolf brethren was copied from a similar shot of Wart being licked by dogs from The Sword in the Stone (1963), and a deer being stalked by Shere Khan was actually Bambi’s mother from Bambi (1942). Animation for the elephants was partially borrowed from an earlier Disney short called Goliath II (1960). Animation from this movie was reused in Robin Hood (1973), and it becomes glaringly obvious in the “Phony King of England” musical number where Little John dancing with Lady Kluck looks exactly like Baloo dancing with King Louie.

Another more subtle reuse of animation from Jungle Book is at the ending of The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (1977) where Christopher Robin and Pooh are walking across a log. This was lifted directly from a shot were Mowgli walks across a similar looking log after running away from Baloo and Bagheera in The Jungle Book.

Reusing animation is a common criticism of animation fans and critics towards movies from that period, but they did it only to keep their films on budget.

Despite these flaws, The Jungle Book was still a sensation with critics and audiences. Actor Gregory Peck, who was then President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, loved the movie so much he lobbied very hard not just to get the film nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, but to actually win the award! He quickly resigned from his position in 1970 after he couldn’t the other members to agree with him. It wouldn’t be until 24 years later when Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (1991) became the first animated feature to be nominated for the Best Picture Oscar. The Jungle Book was nominated for the Oscar for Best Original Song for “The Bare Necessities”, performed at the awards ceremony by Louis Armstrong, but it lost to “Talk to the Animals” from 20th Century Fox’s Doctor Dolittle (1967). The film’s success prompted the Disney animation studio to produce more films and to train and hire new talent. It also served as an inspiration for future generations of animators, such as Andreas Deja, Glen Keane and Brad Bird. When animating Scar in The Lion King (1994), his animator Andreas Deja, longtime fan of The Jungle Book and Milt Kahl’s work, studied Kahl’s drawings of Shere Khan for reference. Will Finn, the animator for Iago in Aladdin (1992), incorporated the motive of the bird losing a few feathers when he got ruffled after the vultures in Jungle Book had some of their feathers fall off when they moved quickly. Sergio Pablos, the animator for Tantor in Tarzan (1999), looked at John Lounsbery’s animation on Colonel Hathi and the elephants for reference. While working on The Incredibles (2004), Brad Bird studied the realistic animation on Mowgli to get a better understanding of how human musculature works. Eric Goldberg, the animator behind the Genie in Aladdin (1992), once claimed that The Jungle Book “boasts possibly the best character animation a studio has ever done”.

On February 14, 2003, Disney released the sequel The Jungle Book 2 in theaters. It was meant to be a direct-to-video release like other Disney sequels, but was given a theatrical release at the last minute. In the sequel, the girl who seduced Mowgli into the man village in the first film was given the name Shanti and a larger role. Despite having the voice talents of Oscar nominee Haley Joel Osment as Mowgli and John Goodman as Baloo and grossing $135 million worldwide, the film was critically panned for basically being a rehash of the first film. There were plans for a third film in which Mowgli and Shanti would go rescue Baloo after he is captured by a Russian circus, but those plans were quickly scrapped. In 1990, the TV show TaleSpin premiered and it featured Baloo as the hero and King Louie and Shere Khan as recurring characters. The show lasted for 65 episodes. Jim Cummings’ voice for King Louie was an authentic impression of Louis Prima; unfortunately, it was too authentic. Disney suffered a legal dispute from Prima’s widow and estate and were forced to pay a hefty fee for using the character in other media, which explains King Louie’s complete absence in The Jungle Book 2. In 1996, Disney premiered Jungle Cubs on ABC, lasting for 21 episodes. The show involved the adventures of younger versions of Baloo, Bagheera, Kaa, Hathi, Shere Khan and Louie. There were two live-action remakes of the film. The first was an action-adventure film released in 1994 (marking the 100th anniversary of the Rudyard Kipling book) with Sam Neill, Cary Elwes, and John Cleese and directed by Stephen Sommers. The second was the 2016 live-action/CG remake directed by Jon Favreau which mixed elements of both the Rudyard Kipling books and the 1967 classic. The cast included newcomer Neel Sethi as Mowgli, Bill Murray as Baloo, Ben Kingsley as Bagheera, Lupita Nyong’o as Raksha (Mowgli’s wolf mother), Idris Elba as Shere Khan, Scarlett Scarlett Johansson as a female Kaa and Christopher Walken as King Louie, who was made a Gigantopithecus since orangutans are not native to India. Mixing a live-action boy with photorealistic CG environments and animals, the film was critically acclaimed, made $966 million worldwide and won the Oscar for Best Visual Effects. One last thing, on December 2010, British artist Banksy created a controversial piece of artwork featuring The Jungle Book characters being prepared for execution commissioned by Greenpeace to raise awareness of deforestation and was sold for £80,000.

That’s all for today! I hoped you found this interesting and learned a lot more about another Disney masterpiece. Don’t forget to subscribe and leave some comments on what you’d me to cover in the future!

Sources